Like any discussion about a particular topic, it is always good to start by looking at the macro concepts that the topic lies within.

Every human, no matter their age, gender, or ethnicity is subject to some basic principles of physiology. I will discuss a couple of these before we dive into the main focus of this blog.

To get started, let’s define load.

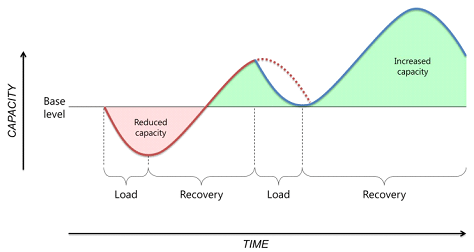

Load is the burden (single or multiple mechanical, psychological, social stressors) that is applied to a human biological system (including subcellular elements, a single cell, tissues, one or more multiple organ systems, or the individual).

Load can be applied to the individual human biological system over varying time periods (seconds, minutes, hours to days, weeks, months and years) and with varying magnitude (i.e. duration, frequency and intensity). – (Soligard, 2016).

The first principle we will touch on is the Overload Principle. It states that cells, tissues, organs and systems adapt to loads that exceed what they are normally required to do.

The second principle we will touch on is the Principle of Specificity.

It explains that overload results in adaptations specific to those cells, tissues, organs, or systems that have been overloaded. Another way of wording this is that the adaptations that the body makes to applied loads are specific to the structures and functions that are loaded.

This is more commonly referred to as the SAID principle. Specific Adaptations to Imposed Demands.

What is very important to remember is that these principles operate in two directions.

The human body and mind adapt to what you do or do NOT do to them.

This is essentially where the layman phase, “use, it or lose it” comes from.

If the body/organism is no longer being challenged with the application of a load, it does not take long before the body/organism realizes that it is wasting energy maintaining the infrastructure it has built. It then deconstructs the infrastructure…all in an attempt to conserve energy.

It is why we do not retain a fitness level once we achieve it.

It also often the reason we see decreased strength, muscle atrophy and decreased bone density (among other physiological traits) in the general population who fall on the more sedentary end of the movement spectrum.

The more we move (with adequate recovery), the healthier our tissues will be and the higher our capacity will be to handle life’s loads.

What are some examples in a health care setting where you would see infrastructure deconstruction?

The obvious ones that come to mind are post-surgery and immobilization (casting, sling) but we see it with almost all injuries due to protection and disuse, etc.

The Earlier, The Better

Taking these concepts into consideration and applying some critical thinking, it makes sense to commence rehab earlier versus later. Think of loss of strength, muscle atrophy and hungry osteoclasts.

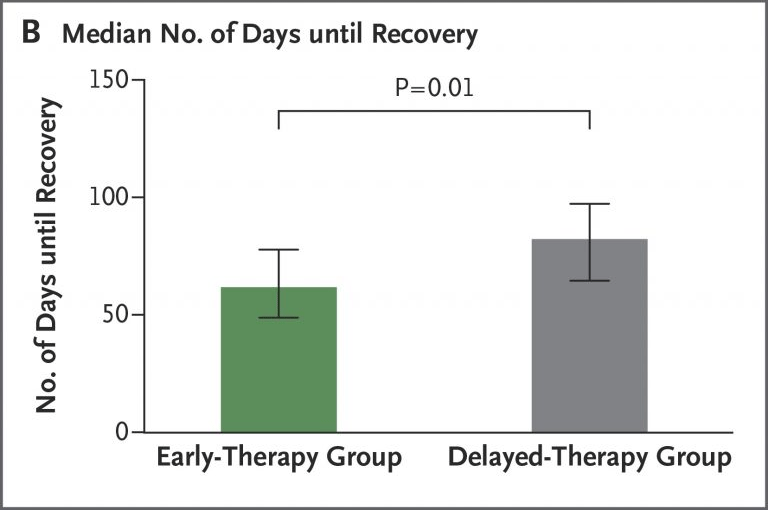

Early versus Delayed Rehabilitation after Acute Muscle Injury (Bayer et. al, 2017)

Randomized study out of Denmark involving 50 amateur athletes with severe injury to thigh or calf muscles.

Return to full activity was more rapid when the rehabilitation program was started 2 days rather than 9 days after injury. A difference of 7 days.

The mean number of days before return to full activity:

⦁ early group was 62.5

⦁ late group was 83.0

Starting rehab 7 days sooner resulted in return to full activity 21 days sooner!

Strategies for Early Onset Rehab

Right now, you are thinking, “He probably thinks that it is best to start rehab immediately after someone has ‘injured’ themselves.”

You would be right.

“Optimal loading is early loading”

Phil Glasgow PhD, PT – Chief Physiotherapy Officer Team GB Rio 2016

To decide what tissue to load, what activity to use, how often to load it, how intensely to load it, you must employ your clinical reasoning. The answers to these questions will be different for every case.

n=1

I could write a book on all the things that are important when prescribing exercises, movements, or activities to a person. Join me in my course if you want the full discussion. In this blog, I am going to focus solely on some strategies that allow you to start the rehab and recovery process as early as possible.

Challenge Unaffected Tissues

To begin rehab early, it is often necessary to let the affected tissue ‘rest’ and stimulate all other tissues of the body.

In these cases, people are extremely acute and moving the affected tissue may be detrimental to their healing.

Challenging unaffected tissues provides an opportunity to limit muscle atrophy and other negative physical changes associated with disuse. This strategy also can help to limit negative psychological feelings that come from being physically limited due to injury/pain.

Challenge Unaffected Tissues

⦁ Lower body and core movements/exercises for people dealing with an upper body issue/injury.

⦁ Upper body and core movements/exercises for people dealing with a lower body issue/injury.

⦁ Challenge the contralateral extremity (cross-education).

⦁ Challenge tissues distal or proximal to the affected tissue(s).

All four of these strategies help decrease the negative effects of disuse due to an injury, but I would like to highlight a couple of pieces of literature related to challenging the contralateral extremity. Also referred to as cross-education (CE).

Cross-Education (CE)

After strength training with the ipsilateral limb, there is an increase in strength levels in the contralateral, non-trained sides (Magnus et al., 2013) and less atrophy of inactive muscles in injured areas of the body (Hendy et al., 2012).

Valdes et al. (2020) ran a small study (n=30) and immobilized one arm for 8 hours per day for 4 weeks. The control performed no exercise on the contralateral arm while there were two other groups who did eccentric strength training and concentric + eccentric strength training respectively.

For the immobilized arm the control group saw a decrease in maximum voluntary isometric contraction (MVIC) of -21.7% while for the eccentric group there was a gain of 12.1% for MVIC.

Case Study

A recreational mountain biker who is two days post-fracture of their right clavicle.

No surgery is needed but immobilization in a sling has been prescribed.

They usually ride 4 days per week and participate in amateur races.

Their racing season starts 14 weeks from now.

When possible, I like to have people perform their meaningful activity as part of their rehab. In this case, they could ride a stationary bike to their heart’s content. They would simply not place their hands on the handlebars. This capitalizes on performing lower body exercises for an upper body injury. It would also enable them to maintain their specific cycling fitness for their upcoming racing season.

To limit the loss of strength in the right arm they could capitalize on cross-education by performing resistance exercises with their left upper extremity. The exercise options here are endless.

They could also perform resistance exercises distal to the affected tissue. They could perform grip strengthening exercises for the right hand. They could most likely perform resisted wrist flexion, extension, pronation, and supination without disturbing the union site.

When you consider a case study like this, it becomes evident that we are essentially able to ‘train’ everything except the affected tissue when someone is extremely acute.

Another great quote from Phil Glasgow PhD, PT:

“Rehab is simply training in the presence of injury.”

Once the person progresses in their recovery arc to the point where the affected tissue is ready for some loading your options multiply exponentially.

Summary

Acting under the assumption that humans are healthier the more they move (with adequate recovery), it is wise to commence rehab as soon as possible after someone suffers an injury.

Challenging the unaffected tissue is the best way to put this strategy into action.

It allows for the body to do what it knows how to do at the injury site while at the same time limiting the negative effects locally and globally of ‘resting’ the affected tissue.

Thank you for reading and I hope you are able to put this strategy into practice!