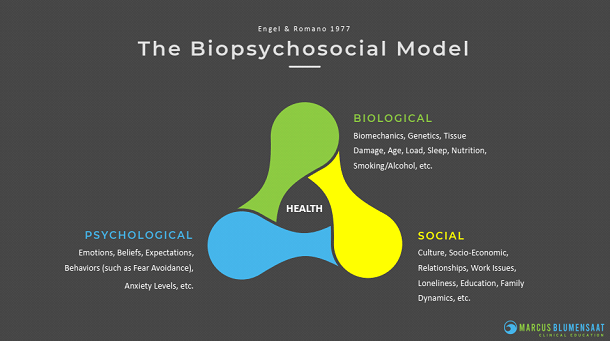

It is widely acknowledged that health is multifactorial and the biopsychosocial model is one of, if not the most often used model to describe this concept.

The BPS model considers biological, psychological and social factors and their complex interactions in understanding health and disease. (Figure 1).

Beliefs are one of the psychological factors that can have a major effect on human physiology.

The ‘power of belief’ has been a topic of discussion in health care and research for years; recently, it seems to be more and more of a hot topic in research, podcasts and blogs.

When looking at health care on a macro scale, the two most common instances where the power of belief is discussed are:

The Placebo effect describes any positive psychological or physical effect that a placebo treatment has on an individual. Though many supplements, modalities and verbal statements have no evidence behind them, they often have positive effects due to the power of belief. Referred to as the placebo effect.

The Nocebo effect is the opposite of the placebo effect. It describes a situation where a negative outcome occurs due to a belief that the intervention will cause harm. Nocebic responses can also be seen in response to a clinician’s use of words.

Let us look at beliefs in a little more detail.

⦁ How are they formed?

⦁ What are the effects of unhelpful beliefs?

⦁ How do clinician beliefs play a part in clinical outcomes?

⦁ How can we help change unhelpful beliefs and behaviour?

Patient Beliefs

Formation of Beliefs

Beliefs about a symptom are formed through:

⦁ Our previous felt experiences of the symptom

⦁ Observing others with similar symptoms

⦁ Information we have learned about the symptom from sources such as the media and clinicians.

The latter two show that our beliefs can pre-exist our own direct experience of a symptom.

Examples of Unhelpful/Erroneous Patient Beliefs

⦁ My spine is unstable – only takes 5% of your muscular strength to stabilize the spine. (Cholewicki et al., 1997)

⦁ My glutes are not firing.

⦁ It is dangerous to slouch while seated.

⦁ Protracted shoulders cause problems.

⦁ I have the incorrect curvature of my spine.

Impact of Unhelpful Beliefs

Studies involving individuals without MSK pain at baseline have found that unhelpful beliefs predict the incidence of future disabling pain.

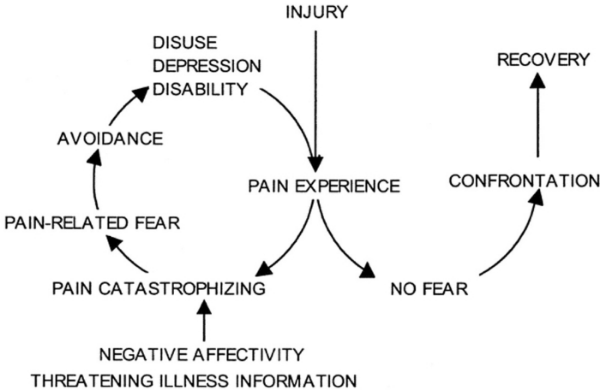

Among people with acute MSK pain, unhelpful beliefs predict the severity of disability over time. Higher levels of pain catastrophizing, fear-avoidance and kinesiophobia at baseline predicted greater pain intensity and disability overtime (Caneiro, 2021).

Chronic/Persistent pain may develop when pain-related fear and avoidance persists despite healing, or when protective responses generalize to novel situations that share features with the original situation (Vlaeyen et. al, 2016).

Clinician Beliefs

Clinicians have an important role to disseminate positive, evidence-based beliefs about MSK pain to their patients.

However:

⦁ Many clinicians hold erroneous/unhelpful beliefs.

⦁ Clinicians who hold erroneous beliefs themselves are more likely to provide advice that reinforces unhelpful behaviors

⦁ Some clinicians feel ill equipped to explore and target the beliefs driving an unhelpful response to pain.

As a result, clinicians may reinforce unhelpful beliefs, behaviours and resultant disability among patients they treat. (Caneiro, 2021).

Because of the potential negative impact on patients, clinicians may be well served by reflecting on their own beliefs in and around pain, health care and human physiology.

Modifying Beliefs

The first step in this process is to attempt to get an idea of the patient’s beliefs about their pain by receiving their history.

“Tell me your story…”

In this discussion, it is important to explore their beliefs, and their emotional and behavioral responses to their symptoms. These are called their explicit beliefs.

In almost every case, the patient’s history is the most vital source of information you will have.

The second step involves using physical assessment with exposure to postures, movements, or activities of daily life (ADLs) that are provocative, feared or avoided by the patient.

By observing the patient perform these, you will be able to watch their behavioral response to the stimuli to learn more about their beliefs.

Specifically, implicit beliefs that drive behaviours may be revealed by this exposure.

i.e., exposure to the target posture, movements or ADLs may elicit protective responses within the body that the patient may not be aware of.

Examples: avoiding applying load, changes in breathing, wincing, etc.

Once you start to have a general idea of the patient’s beliefs, you can begin to work with them to modify them.

Modification of beliefs can be achieved in multiple ways and can begin at any point in your session.

⦁ Clinician provided education – reassurance, dispelling myths, proposing different ways to respond to pain → “it is okay to feel some pain”, etc.

⦁ Education resources – stats on asymptomatic people who have clinical findings on scans, videos for OA and exercise, etc.

⦁ Graded exposure – performance of a feared or provocative posture, movement, or activity with a different mindset towards it and/or a slightly different way of performing it (perhaps omitting the avoidance behaviour).

This form of behavioral learning is repeated so the patient can build confidence and learn a new way of viewing and experiencing the feared posture, movement, or activity.

The new nonthreat associations that are formed may subsequently generalize across time and contexts.

For this generalisation to occur clinicians should encourage patients to integrate their new strategies immediately into their daily life to build self-efficacy and strengthen the new representation.

Exposure-based treatments have been shown to be effective in various pain syndromes, both in adults and youngsters (Vlaeyen et al., 2016).

You can tell someone that they are safe but it is more likely to register with them if they experience that they are safe.

Using graded exposure movements in this manner is a great way to slowly change peoples’ expectations and beliefs around movements and postures. The performed movement violates their negative expectations and can lead to the creation of a more positive expectation in the future.

Movement and/or exercise can give someone confidence to use their body by confronting and proving wrong their unhelpful beliefs and expectations.

Always remember that n=1.

Nobody wants to be repeatedly told that they are wrong. You do not always have to correct every wrong statement that a patient makes or point out every single unhelpful belief that they have.

Find the main unhelpful belief that a patient has and address that belief with education and mechanical interventions.

You do not want to ‘lose’ the person. Maybe the unhelpful belief came from a trusted health care professional that they have seen for years. Use your best judgement when deciding if you are going to challenge their unhelpful beliefs.

Summary

Clinical practice guidelines recommend addressing erroneous/unhelpful beliefs as the first line of treatment in all patients presenting with musculoskeletal pain. (Lin et al., 2020).

Patient and clinician beliefs can create both negative and positive effects. My hope in raising your awareness to the power of belief is to get you to start reflecting on your patient’s, and your own, beliefs and how those may be affecting clinical outcomes.

References

Caneiro, J., Bunzli, S., & O’Sullivan P. Beliefs about the body and pain: the critical role in musculoskeletal pain management. Braz J Phys Ther., 25(1):17-29. doi: 10.1016/j.bjpt.2020.06.003.

Cholewicki, J., Panjabi, M., Khachatryan, A. (1997) Stabilizing function of trunk flexor-extensor muscles around a neutral spine posture. Spine, 22(19):2207-12. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199710010-00003.

Lin, I., Wiles, L., Waller, R., Goucke, R., Nagree, Y., Gibberd, M., Straker, L., Maher, C., O’Sullivan, P. (2020). What does best practice care for musculoskeletal pain look like? Eleven consistent recommendations from high-quality clinical practice guidelines: systematic review. Br J Sports Med., 54(2):79-86. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2018-099878.

Vlaeyen, J., Crombez, G., & Linton, S. (2016). The fear-avoidance model of pain. Pain, 157(8): 1588-1589. doi: 10.1097/j.pain.0000000000000574

Vlaeyen, J., & Linton, S. J. (2012). Fear-avoidance model of chronic musculoskeletal pain: 12 years on. Pain, 153(6), 1144–1147. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pain.2011.12.009